Last Updated on March 16, 2024 by Lea Anderson

“This movie is really getting at something that’s been in and out of my dreams for years,” Wes Craven told Fango writer, Marc Shapiro back in 1990. “They were visions of houses, finished and unfinished, that branched off into long, winding galleries. Nightmare on Elm Street got into that dream to a certain extent, but this film is taking it all the way.” He designated The People Under the Stairs “domestic horror,” apropos not just because the film is primarily set in “a house of real-life horror,” as Shapiro put it in the January, ’91 issue of FANGORIA, but because of what the symbology of the house- the domestic sphere- signifies about America as a whole. After all, the word ‘domestic’ refers to both household and nation.

This wasn’t new terrain for Craven—more a type of homecoming. In some ways, the film is a fairytale epic no different than those you’ve ingested a million times before, but what made The People Under the Stairs “ahead of its time,” as actress, Kelly Jo Minter described in the Shudder documentary, Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror, is that it wields the master’s tools (the Hero’s Journey chief among them) to symbolically destroy the master’s house. Craven often cited Night of the Living Dead as one of his major influences, and it’s clear that Poindexter “Fool” Williams (Brandon Adams) is his answer to Duane Jones’ Ben. Long before Get Out was a twinkle in Jordan Peele’s eye, Craven rescripted the 1968 classic’s devastating ending to give Ben, Fool, and the audiences they represent, the catharsis we so deserve.

Shapiro also called the project “a return to the themes of the films that made his early reputation,” referring, of course, to The Last House on the Left, The Hills Have Eyes, and the original A Nightmare on Elm Street, all of which feature Craven’s most enduring motifs and obsessions: the gothic, sometimes horrifying nature of the family unit manifest in either the presence or absence of the gothic architectural structure that is the family home. At its core, The People Under the Stairs is an eviscerating commentary on class warfare, gentrification, and the general perversity of imagination beget by white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

Inspired by a 1978 Los Angeles news story where two abused children were found and rescued by burglars, the film’s “haunted house” isn’t haunted by spirits so much as the utter madness of those who live there. Homeowners, Man and Woman (played magnificently by Everett McGill and Wendy Robie) are incestuous, cannibalistic siblings who refer to one another exclusively as “Mommy” and “Daddy” (a nod to the Reagans and old Southern tradition). For years, they kidnapped, abused, mutilated, and incarcerated children in their labyrinthine house, among them, Alice (A.J. Langer) and Roach (Sean Whalen). They’re also- of course- landlords who “own…half the ghetto,” including the decaying building where thirteen-year-old Fool lives with his older sister, Ruby (Kelly Jo Minter), her kids, and their cancer-sick mother. When Ruby’s friend, Leroy (Ving Rhames), reveals the family’s impending eviction and their landlords’ (read: capitalism’s) bloodthirst, Fool is recruited to break into their house and assist him in stealing the couple’s mythologized rare coin collection.

The story seeks to complicate status quo ideas about criminality and poverty; how what we call crime is most often a response to the conditions of poverty- which is to say, the conditions of capitalism- rather than an indicator of moral character. Craven’s films almost always play with prescriptive tensions around illusions of safety and the inside/outside boundary (think Scream and the idea of the call coming from inside the house, or Hills, where travel leaves one vulnerable, exposed) but, as he said, The People Under the Stairs takes it “all the way.” He flips the standard dynamic of the home invasion narrative to render the “invaders” heroic for exposing the monstrousness of the homeowners. Beneath its façade, the Inside (suburbia, the house, the white body invested in its own whiteness) is an intensely nightmarish place. Inside, “every cabinet has a lock on it.” Shatterproof windows padlocked from the outside, an electrified doorknob, booby traps, secret passageways, cannibals locked in the basement, Roach- escaped from the basement- wreaking havoc in the walls, and their “little angel,” Alice, less a person than a doll for Mommy to impose her will upon.

Mommy is pathologically obsessed with cleanliness and control (Craven described her as “very clever” and “manipulative”) while Daddy is “more brutal and beastly.” Alice tells Fool that no one has ever escaped the house; that the people in the cellar were kidnapped by Mommy and Daddy while searching for “the perfect boy-child,” but they all “turned out bad. Some saw things they weren’t supposed to; others heard too much; others talked back. Daddy cut out the bad parts and put the boys in the cellar one by one.”

This represents one of many references to the Three Wise Monkeys of Buddhist tradition, from whom the maxim, “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” derives, and which functions as the de facto motto of Mommy and Daddy’s house of horrors. Many readings exist, but they, of course, adhere to its most carceral interpretation. Anyone with the power to reveal the truth about their twisted interior world is considered “evil,” a manipulation tactic valued by colonial religious fundamentalism and the structural foundation of the haunted house that is American white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

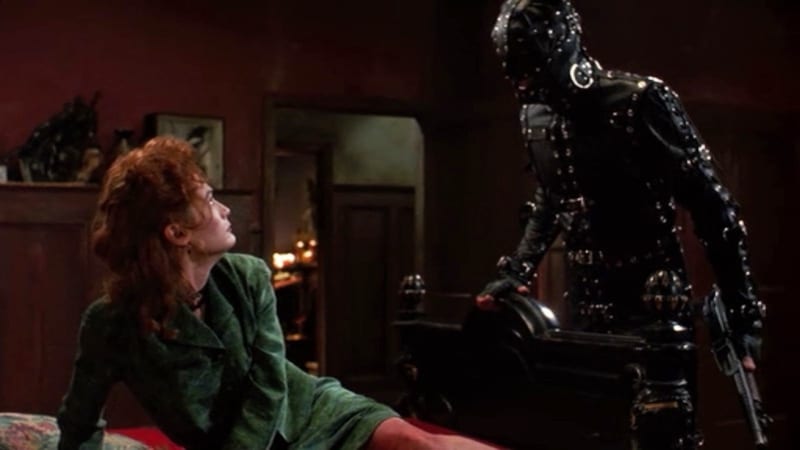

As stand-ins, Man and Woman reflect the weaponization of white cis heteronormative binary gender roles and the violent psychosexual rage they produce. There is a parallel in the way Mommy unleashes their beloved, flesh-eating rottweiler, Prince, and her control over Daddy’s more brutish impulses. When Alice is perceived as “bad,” Woman threatens her with the subtle suggestion of punitive rape, exhibiting how Man’s “tension” is hers to manage and harness. The brilliance of the leather bondage suit is how it so successfully signifies the shift between Man’s “outside” and “inside” faces; how the act of hunting, of imposing dominance, of shooting his shot all over the house in a performance of “protecting” Woman—how all this is primarily a sublimated sexual act.

To Shapiro, Robie described her and McGill’s characters as having “a guise of morality…. They show a very normal, very conservative face to the world. But when they go back inside the house and their masks come off, we see them for what they are: crazed, control-hungry, murderous monsters.” Craven confirmed this estimation. “The house, with all its claustrophobic spaces and hiding places, stands for civilization run amuck. The generations that have lived in it have gotten more and more crazy until the present one is totally locked into madness.” In the film’s Blu-ray commentary, he flat out states the house represents “the whole society of the United States.”

Thirty years since its release, this madness has only become more legible; a white woman getting away with literal murder by distracting cops with tea, cookies, and feigned politeness, more believable.

The camaraderie between Fool, Alice, and Roach tells a story about solidarity across race, gender, and class. None could hope to either survive or escape without each other. Fool comes to understand the cannibals in the basement- the people under the stairs- aren’t actually monsters but were made monstrous by Mommy and Daddy, drawing a common thread between conditions of marginalization (of race, gender, class, ability) and the condition of monstrosity. With help from Roach, Alice, the people under the stairs, Ruby, his grandpa (Bill Cobbs), and all those displaced and impoverished by the couple’s greed, Fool defeats Mommy and Daddy, blows the house up, and frees those incarcerated within its walls. The final shots are of everyone- monsters included- dancing and celebrating as money and gold literally rain from the sky.

The legacy of The People Under the Stairs and its influence on contemporary horror can’t be overstated. It’s felt in films like 2020’s Vampires vs. The Bronx, and 2011’s Attack the Block, particularly in John Boyega’s character, Moses. Ryan Murphy revived the bondage suit to great effect in American Horror Story: Murder House, while last year’s Them tackles similar themes to lesser effect (Craven was intentional about limiting onscreen brutality). But perhaps most notably, the film was a profound influence on Jordan Peele and his conception of both Get Out (in which a Black protagonist must escape the sunken place as situated beneath a haunted house reflective of neoliberal white America) and Us (where class hierarchy is also rendered architecturally literal).

In Horror Noire, Peele describes how the film so successfully “captures…Black fear of white spaces” and how Roach being trapped in the walls “was the most powerful and terrifying part about that movie. You look at Get Out, it’s clear that my deepest deepest fears come from this idea of confinement.” What makes The People Under the Stairs so ripe for a revisit is its devastating relevance, how aggressively timely it remains thirty years later, and the fact that Fool gets out. He “speaks evil” in the sense that he speaks truth to power, escapes the inescapable house, and in turn, gives us hope that someday we might all be free.

If you're in the mood for a revisit or a first time watch, click below to stream now: