The release of Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu is the culmination of a lifetime of ambition and about a decade of planning. The filmmaker, who first viewed F.W. Murnau’s silent vampire classic when he was a child, has been working toward realizing his own version since around the time his first feature, The Witch hit the scene in 2015.

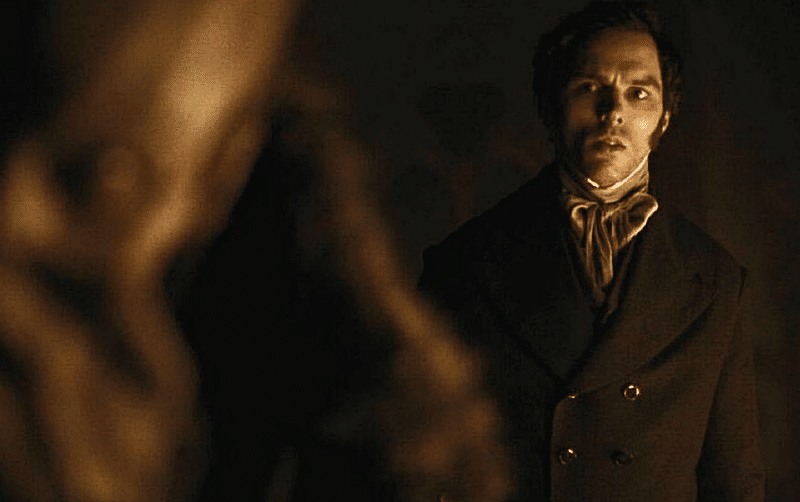

Now it has emerged on screen, set in 1838 in the fictional German town of Wisborg, with Bill Skarsgård as the ghoulish Count Orlok, Lily-Rose Depp as Ellen, the object of his twisted affection, Nicholas Hoult as Ellen’s husband Thomas, who first meets Orlok on real-estate business in Transylvania, and Willem Dafoe (who portrayed original Nosferatu star Max Schreck in 2000’s Shadow of the Vampire) as occult expert Professor Albin Eberhart Von Franz. Eggers spoke to Fango about the inspirations and craft of Nosferatu, and the pressures of taking on a landmark of cinema; you can read more of this interview in issue #26.

You’re a lifelong devotee of the silent Nosferatu; are you also a fan of the 1979 Werner Herzog version?

I am; less so, but I watched it a ton as a teenager. I’ve tried over the last ten years to not watch it, during the development of my own movie, though.

How have Nosferatu and your vision for it changed over the many years you’ve been working on it, both thinking about the movie and actively developing it?

As a teenager, I realized that it was not actually that Expressionist of a film for an Expressionist film, and that F.W. Murnau, [producer/production designer] Albin Grau and his collaborators were interested in romanticism. They filmed on locations partially because of financial constraints, but that added a kind of realism to their movie that is different from other German Expressionist films. So originally, I wanted to Caligari-cize it and make it very Expressionist—which is very much not what I’ve done now.

But from that time of about 10 years ago, when I started working toward making the film, I haven’t changed it much since then. There was a time that was spent trying to really understand the period and the occult philosophy that my Van Helsing character [Von Franz] would have, and to understand the folklore and folk vampires better.

I wrote a novella as I was breaking the script, to enrich the backstories of the characters and their relationships, in order to make it my own. Since I found that, it’s gotten better, it’s gotten sharper, but it has pretty much stayed the same thing, where it is very much Ellen’s story, about a woman who is as much a victim of 19th-century society as she is of the vampire. And this demon-lover relationship she has with Orlok.

Do you think it’s a better film now than it would have been if you had made it years ago?

I hate to be the type of person who says that everything happens for a reason, which is kind of against my nature. But the timing of how this film worked out, with the cast we have, seems kind of perfect. Had I actually gotten the green light on one of those other versions, I don’t think the movie would have been anywhere near as strong. Certainly I wasn’t as adept a filmmaker at the time. I’ve learned a lot, on The Northman particularly; it was like, I finally learned how to make a movie after that. I feel I am now a director, and I’m not just trying to convince financiers that I’m a director [laughs].

Can you talk about the conception of the visual scheme and the sets? They’re truly impressive and evocative.

Thank you. The moonlit look that [cinematographer] Jaren Blaschke and I have been developing over the past couple of movies is more black and white, which is technically how your eye sees it. You may experience more color because you know the colors of objects, but when you are in moonlight, it’s pretty desaturated, so that’s what we were going for. And in terms of the sets, we were just saying, “What would a northern German Baltic city be? What would Transylvania be? What would the castle be?” and we built virtually everything.

Craig Lathrop, the production designer—his finishes are so excellent that oftentimes, people think we’re using locations when we’re not, and part of that involves getting the architecture and the period exactly right. Another facet is for Jaren and I to have the control to put the camera where we want it, and do these long, complicated shots that often involve moving walls during the take. And we certainly couldn’t do that in a real castle.

How much research into the period did you do when you were writing the script?

Massive amounts of research. There’s no way for me to fully invest in the world and be able to communicate it to an audience without understanding it to the fullest of my ability. So I did tons of research on my own, and that was put into the script, the dialogue and the style of the language. Then all of my heads of department also did a tremendous amount of research, particularly Craig and Linda Muir, the costume designer. We also brought on Florin Lazarescu, who is best known in the West for the screenplay for Aferim!, and he was our sort of Romanian consultant who worked with us on a lot of that stuff.

What is it about historical horror in particular that fascinates you?

I don’t know, really. I mean, I like building worlds; I enjoy the act of doing it, and I like learning about other eras. I get enough of today today. But also, for me, it’s easier to believe in vampires and ghosts and witches and werewolves in the past, rather than in a modern setting. Not to say that there aren’t contemporary films that work very well with these kinds of creatures, but it is just more satisfying for me.

What was the most challenging part of this whole project?

Obviously, there’s just the weight of doing Nosferatu, which, at times, was a bit overwhelming and intimidating. You become embarrassed with your hubris when you do something like this. I know that myself, Bill Skarsgård, David White, who designed Bill’s makeup, and Robin Carolan, the composer—we all particularly felt the weight of, “Oh God, we’re doing Nosferatu!”

There was also Lily-Rose Depp’s body work, which, by the way, is all real. She worked with Butoh choreographer Marie-Gabrielle Rotie to do all those contortions, and they’re not CG-enhanced. That was a lot of work, and also getting Bill’s makeup to make sense and work for the camera.

Believe it or not, the Transylvania sequence in the village was also really difficult. Casting and costuming that were among the greatest challenges of the film. It may have seemed sort of simple, but trying to do it accurately was incredibly challenging.

Do you have any other classic characters you’d like to tackle beyond this one?

I’ll keep that to myself. But in a world where, with the current climate, no one seems to want to greenlight anything that’s not some kind of IP, I certainly should [laughs].

How do you see the current state of horror today? What’s your point of view on that?

I think it’s in a pretty good place. Because of the fact that horror movies under a certain budget tend to perform well, it has given filmmakers a lot of freedom to tell more interesting stories through genre. There’s always crap, but there’s quite a bit of good stuff out there.

You talked about the mental challenge of tackling a classic. At the same time, do you think there might be a new generation of filmgoers who are not familiar with Nosferatu, for whom this might be their first exposure to the character and the story?

I hope so; that would be awesome, you know? And hopefully it’ll bring them to silent cinema and get a new generation of young people interested in that, and they can see what they can learn from it, certainly young filmmakers.

What do you think young filmmakers could learn from silent cinema these days?

By the end of the silent era, the visual storytelling was incredibly strong. I’m not the first person to say that when talkies came in, the staging and the camera angles became less sophisticated, and it took a while for it all to come back together again. But there is something really essential about silent cinema, and a film like Murnau’s The Last Laugh that has very few intertitles. You can see how you can communicate with just imagery, you know? I do this sometimes—Hitchcock did it religiously—but it’s good when you’re making a film to watch it without the sound and see if you can still understand the story.

Nosferatu is now in theaters. For more with director Robert Eggers and star Willem Dafoe, check out our recent interview. (And read the rest of this interview in our Winter issue, FANGORIA #26.)