This editorial contains detailed spoilers for Longlegs, as well as mentions of child abuse, sexual assault and domestic violence.

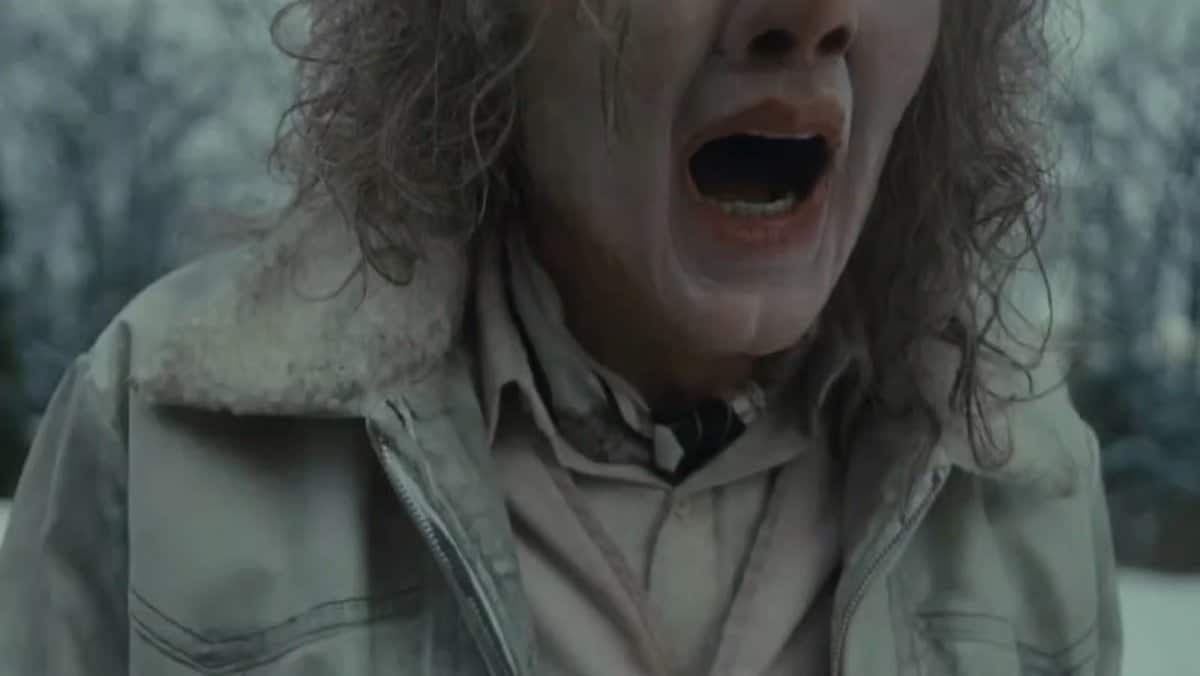

Osgood Perkins’ labyrinthine Longlegs, one of FANGORIA's top horror films of 2024 (stay tuned for our full list!), opens with every parent’s worst nightmare; a playful stranger with malicious intent, preying on the innocence of a naive child. A backyard, smothered in purest snow, becomes a hunting ground for a beast who is at once both familiar and frightening – a foe playing dress up, crudely, as a friend.

Many first reactions to Longlegs saw viewers reacting in similar ways, commenting the film was terrifying, disturbing, evil emanating from every scene – but that they immediately wanted to watch it again. Us horror freaks know this feeling all too well, and it’s an old one.

For many of us, our first experience with the horror genre came as children – whether it be tween sleepovers spent hiding from the gore of the Deadites in Evil Dead, or accidentally waking up to parents watching a VHS rip of The Blair Witch Project in the living room late at night, the choking fear comes first, sometimes lasting for days, but soon gives way to something arguably much darker – I want to see that again. Longlegs evokes that very primal, childlike fear in the deepest part of our id: what if that knocking wasn’t just the wind? What if that shadow really did move by itself? What if that nice man really… isn’t so nice at all?

Longlegs, a film at its phantasmagorical core about familial abuse in its various forms, makes children of us from the start. FBI Special Agent Lee Harker (a twitchy Maika Monroe), our traumatized audience stand-in, is proof of this, continually forced into the role of a child, tearfully facing those fears of shadows in the dark and strange men in the garden. Our first impression of Lee is not as a strong, fearless and confident woman, but as a scared little girl, both in the film’s opening flashback and when we see her decades later.

In her first on-screen assignment, Lee’s concerns are immediately ignored by her male partner, Agent Fisk, who firmly takes the lead on the case and establishes himself as the one who takes action. Lee reluctantly takes a back seat, unable, or unwilling, to insist on her gut instinct. When invited (or, more appropriately, forced) into the home of Agent Carter, Lee’s childishness is evident by the way she aligns with the other minor in the home, sitting awkwardly in little Ruby’s bedroom while the grown-ups talk downstairs. Her vulnerability is continually demonstrated by all the hallmarks of a young girl’s life; cutesy birthday cards, domineering men and, of course, Mommy’s strict reminders to always say her prayers.

But naughty Lee doesn’t say her prayers, not even once. Because they scared her, as they should. In the world of Longlegs, the places that should be safe for children – a bedroom, a birthday party, under the watchful eye of a pious woman – are not. The children of Longlegs are constantly at risk from adults and the institutions who are supposed to protect them – especially the ones who claim they are the holiest. Lee’s devoted mother Ruth, with her bloodied habit and thousand yard stare, represents a mother fully complicit in religious institutional violence – maybe not to her own children, but to others she is meant to shelter.

In Ruth, we see a refusal to speak up that is arguably just as damaging as the actual abuse itself and, sadly, all too common. While various experts have long been skeptical of the legitimacy of Satanic ritual abuse, there is absolutely no question that child abuse within many religious institutions is rife. When Ruth dons her garb, pious and prim, she spreads Longlegs’ evil as a woman of the Church, abusing the trust of god-fearing families to spread the good word of the Father – but not the right one.

If Lee plays the child, by the rules of Longlegs’ own MO, she must surely have a mommy AND a daddy. After all, the American Dream dictates as such. The role of the father in horror is a long and storied one, yet somehow often sidelined in favor of discussions on monstrous mothers and a perversion of some kind of inherent maternal spirit that all women are supposed to be tethered to. Whether Longlegs is Lee’s biological father or not will surely be prime fodder for lively and divisive debates at the horror dinner table. One thing is for certain: there’s no denying that Longlegs, aka Dale Kobble or, as he once tellingly refers to himself, Lee Harker, plays the role of a father in some sick and twisted form. The very title of the film should make that obvious enough.

Longlegs is a creator, expertly crafting sentient, exquisitely lifelike dolls in his image (at least internally). The Man Downstairs is the man of the house, a diligent daddy working hard to keep his own surrogate family safe from the darkness inside. He emotionally longs for the love and touch of his own demonic father, following his orders just as Lee follows the clues laid out for her. He operates in a world where the symbol of the father – be it God, the Devil, Anton LaVey, or the portraits of presidents hung prominently as a reminder of serving the constant watch of powerful men – holds power over all. Longlegs’ obsession with triangles comes not only from its distinctive symbolism in Satanic ritual, but because of its three sides; Daddy. Mommy. Baby. The perfect nuclear family. When Lee takes her psychic test in the dingy dark of the FBI station, her word associated with this image of the triangle, without missing a beat, is father.

For many children, the father is the first protector, a man bigger than god, with loving arms that stretch as far as heaven is wide. For others, the father is hell on earth, his legs descending down into inferno. We’re inclined to believe that, for Lee, it is most certainly the latter. Throughout Longlegs, fathers are the crux of cruelty, and it is no coincidence (and almost certainly no surprise) that Longlegs’ demon dolls exert their influence most intensely over the fathers of these picture-perfect households.

As it absorbs the seeping sins of Longlegs, the family home becomes an arena of violence, with women and children the first to suffer. Bodies are bent, broken and twisted beyond recognition because, as it is in so many corrupt institutions, the cruelty is the point. Furthermore, it is easy to see the vicious specter of domestic violence burrowed deep within Ruth, her dazed facade breaking first with the bitingly bitter revelation that Lee “was allowed to grow up” – an agonizing admission from a mother who took the sting of the belt in place of her daughter.

As we entangle ourselves further into Longlegs’ web of paternal perversion, an even danker rot reveals itself, one that is essential to consider when reading the film as a comment on institutional abuse. From his first introduction in Lee’s frozen yard, Longlegs’ interest in children is distinctly coded as sexually abusive – he may never touch these children with his own ghoulish hands, but his gentle kisses on their doll-proxy foreheads, his cooing murmurs of “little angel” and “birthday girl” and his promises of playtime are all trappings to lure in the innocent for the most sickening of reasons.

Longlegs imbues his dolls – or, victims – with a part of himself, ensuring the cycle of familial trauma and abuse continues through young girls and their monstrous fathers. A sickening 911 call from one of them eerily, almost gleefully, details that “the best time to do it was when her eyes were closed” – a nightmarish sneer that needs no further explanation as to what heinous act it refers to. And Carrie Anne Camera, happy as peaches, displays many of the explicit hallmarks associated with survivors of such abuse – dissociation, suicidal ideation and a loving, contradictory attachment to the father figure who took everything from her.

Then there’s Lee’s own memories of Longlegs, memories that send shockwaves through her psyche after digging through the tokens of her childhood. Alongside her own dollies gathering dust lies a trauma that Lee has buried deep for years. In the film’s surreal birthday party climax (notably, one of the last birthdays before the average girl hits puberty), Lee makes the choice to end the cycle, freeing herself from the fate laid out by her mother by shooting her dead, and turning her gun on the doll, in which lays the last vestige of Longlegs.

But she either can’t, or won’t. Longlegs’ final scene forces us to face a fact that many of us, with the existentialism of age, simply do not want to admit – we all risk becoming our parents. Just as it is futile to attempt to escape our inherited genetics, or to outrun the scars they leave on our souls, Lee cannot escape the Satanic influence of the pallid psychopath and his disembodied grasp. It is a fate that Lee was resigned to the minute she met the tall, tall man with his long, long legs – a fate she knows she has no choice but to accept. Because, after all, Daddy Longlegs knows best.